Jackson Pollock Blue poles 1952, oil, enamel, aluminium paint, glass on canvas, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra © Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Licensed by ARS/Copyright Agency.

Jackson Pollock’s monumental painting Blue poles is recognised today as an Abstract Expressionist masterpiece. The work is a prime example of his unique approach to action painting.

He started Blue poles in 1952 by working on the floor of his studio, a converted barn on Long Island in the United States of America. It was painted on a large roll of prepared canvas using commercially produced enamel and aluminium paints. It measures 213 centimetres high by 489.5cm centimetres wide and weighs 99 kilograms.

Blue poles was purchased from New York collector Ben Heller for Australia’s national collection in 1973.

Jackson Pollock painted Blue poles using flung and dripped lines of brightly coloured household paints. We see the vivid brilliance of ultramarine blue, the deep warmth of cadmium yellow, a reddish orange like tangerine, thin drips of white, puddles of thickened cream and squiggles and splashes of black. These paints are standard colours, like those we might buy in cans from a hardware store.

Pollock also used a shiny silver-coloured paint manufactured from aluminium particles. He was excited by the textural contrast this metallic paint formed in combination with ordinary oil paint. Certain colours were left to dry before he added further layers. Others were layered wet on wet to mix on the canvas, the paints mingling, their intersections forming pockets of marbling. The effect of this seemingly random mixing of colour and Pollock’s rhythmic actions means that there is an equal impression of chaos in a small section as in the overall painting.

Pollock painted Blue poles when he was forty years old. A few years earlier he had made the radical shift from working on an easel to unrolling lengths of canvas onto the ground. For Pollock, this impulse brought together his experience working on murals during the Great Depression, his long interest in the sand paintings of south-western Native Americans and the vast plains of his unsettled childhood in Wyoming, Arizona and California.

With his pivotal shift in approach and scale, Pollock’s work became increasingly abstract, as he relied on his unconscious for guidance. His figurative paintings had been darkly symbolic, drawing on Jungian archetypes excavated through a decade of analysis and treatment for recurring alcoholism and depression. He distilled his life experience in this late stage of his career into physical gestural rhythms, with his figurative symbolic images becoming obscured beneath layers of energetic linework.

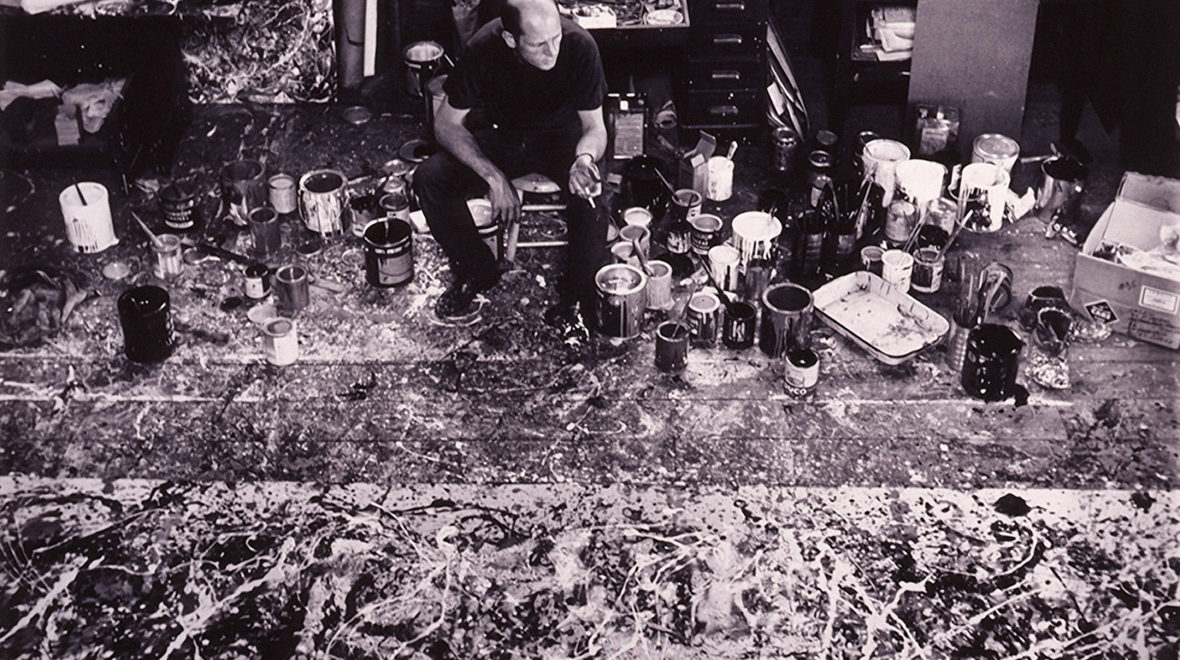

Jackson Pollock working on a painting in his studio in 1950. Photograph by Hans Namuth

The different thicknesses of the strings and ropes of colour reveals the different hand movements that Pollock used to apply the paint. He had been interested in experimental techniques of painting since the 1930s, and with the canvas now lying flat, Pollock rarely touched the surface anymore, instead applying the paint using sticks, dried paintbrushes, trowels, turkey basters and syringes. Using smooth twists of his right wrist Pollock would flick, squirt, pour and drizzle the runny paint. This new approach resulted in a series of what were later described as his ‘drip paintings’, in which the drawing was all done in the air above the canvas.

The runny texture of the low-viscosity paint stopped it from breaking into smaller droplets. Some colours have landed like gooey strands of melted mozzarella cheese or long drools of spittle. The entire surface is covered with these lines, leaving no one spot for our eyes to rest, forcing them to keep moving. In this way Pollock’s painting holds you in the act of looking and gives you time to think and make connections.

Because much of Blue poles was painted with the canvas flat on the floor, gravity has not pulled the paint into drips except for one thin layer of white paint, produced when Pollock temporarily tacked the canvas up on the wall of his studio. As the rest of the layers have dried, some paints have formed a puckered surface. The tiny ripples in the cadmium yellow and the silvery aluminium paint add to the texture and energy of the painting.

Also buried under the stratum of paint colours are curved fragments of glass. Hans Namuth’s iconic 1951 documentary on Jackson Pollock details how he liked to use ‘sand, broken glass, pebbles, string, nails or other foreign matter’ to build up the textured surface of his paintings. Filmed at Pollock’s rural home in Springs, East Hampton, in 1950, the documentary captures Pollock’s process, confirming how he worked by instinct and intuition.

Pollock didn’t make preliminary drawings but described his painting method as ‘direct’. In Namuth’s film, he paces up and down the length of the canvas, smoking, as he flicks out his whiplash lines from a can of white enamel. We watch the painting take shape, precise pale lines seem to magically appear over the top of earlier dark forms. At times we hear his voice intoning a series of statements: A method of painting is a natural growth out of a need. I want to express my feelings rather than illustrate them. Technique is just a means of arriving at a statement.

Blue Poles Described

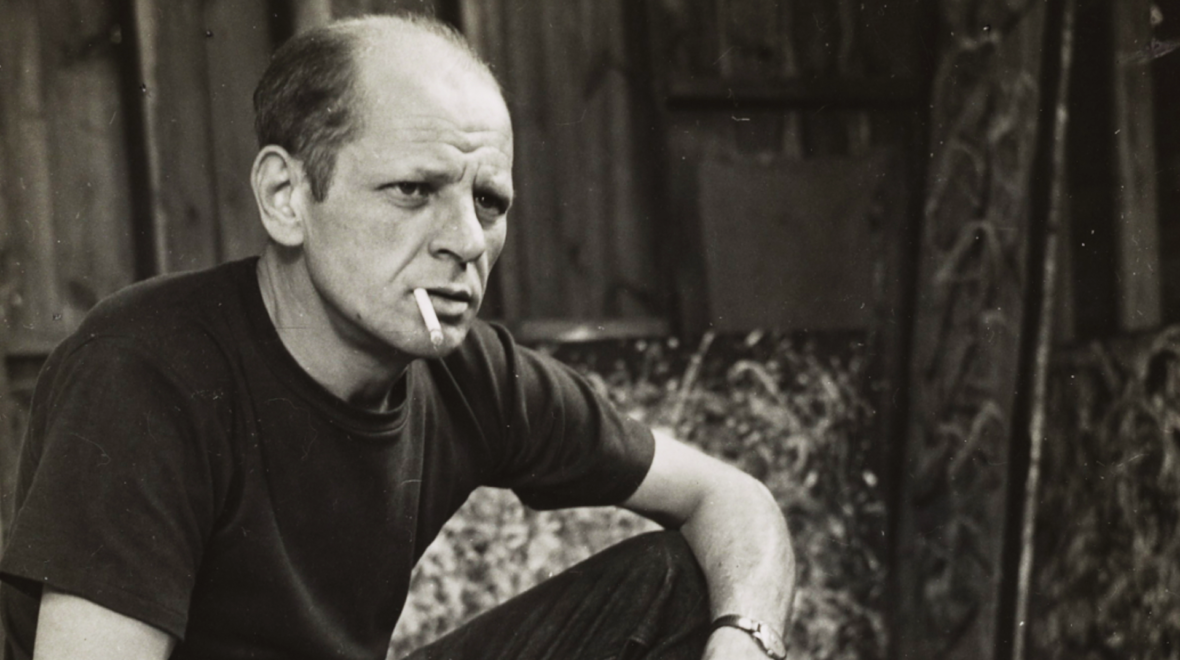

Pollock’s career had skyrocketed after a feature in the August 1949 issue of Life magazine dryly asked, ‘Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?’. Although the article was supposed to be provocative, America loved the myth of the cowboy painter, with the 37-year-old Pollock photographed standing in front of an earlier 5.5-metre-long action painting. He is wearing paint splattered jeans, arms crossed, with the ubiquitous cigarette dangling from the right-hand corner of his mouth.

Blue poles was first exhibited as ‘Number 11, 1952’ in Pollock’s solo show at Sidney Janis Gallery in New York in November 1952. Two years later, he gave it the descriptive title ‘Blue poles’, which refers to the eight dark vertical stripes that interrupt the swirling surface. These evenly spaced ‘poles’ stretch across almost whole height of the canvas and each is crossed with three or four horizontal lines. They are all placed on slightly different angles, tilted to the left or right, suggesting the listing masts of ships or swaying tall trees.

Although it was one of the last major paintings made by Pollock, Blue poles recalls the compositional teachings of his earliest teacher and mentor, Thomas Hart Benton, who emphasised the idea of a vertical structure that anchors a spiralling form. Added towards the end of the painting process, the strong blue-black poles were formed by pressing the wet edge of a painted length of wood onto the canvas surface. These thick, insistent lines were then overlaid with additional flung lines of cream, tangerine and black paint.

Blue poles embodies Pollock’s ideas about pure painting and the unconscious. The energy and scale offer us the possibility of stepping into Pollock’s world. It brings together his complex experience of life, alternating between darkness and light, between turmoil and elation. The intense energy generated by his contribution to action painting created something new and vital in American art that continues to resonate today.

Sarina Noordhuis-Fairfax is the National Gallery’s Curator of Australian Prints and Drawings.

More