JACKSON POLLOCK’S Blue poles was acquired by the National Gallery 50 years ago. SEBASTIAN SMEE investigates what else entered the collection in 1973.

The list of new acquisitions made by the National Gallery of Australia in 1973 runs to hundreds of pages. A Mayan food grinding table in the form of a jaguar is just one more item in an inventory that also includes dozens of photographs by Yousuf Karsh, scores of prints by postwar Americans Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg and hundreds of works by Australian artists including Grace Cossington Smith, Peter Powditch and Patricia Englund. Among the works from non-Western cultures on the list of 1973 acquisitions (apart from the Mayan food grinding table) are dozens of Javanese puppets and a canoe prow figure from the Solomon Islands.

Jackson Pollock’s Blue poles 1952 also appears on the 1973 list. It was one of the items purchased in July, immediately after abstract works by Grace Crowley and Eric Wilson and before figurative prints by Hal Missingham and Roy Dalgarno. It is, in the context of the Gallery’s inventory, just another artwork. But of course, Blue poles quickly came to occupy a place in the Australian imagination that was so much more. It became a target, a flashpoint, a symbol of something bigger — laudable ambition or reckless stupidity, depending on how you saw it. Later, it became a ‘destination painting’ and later still, a commodity with an increasingly outlandish dollar value. In 1973, the AUD $1.3 million paid for the painting was a record for an American artwork. News of the sale caused a sensation even in the United States and was credited with triggering an exponential rise in international art prices that today shows no sign of abating. In Australia, it was also held responsible (somewhat hyperbolically) for helping to bring down the Whitlam government.

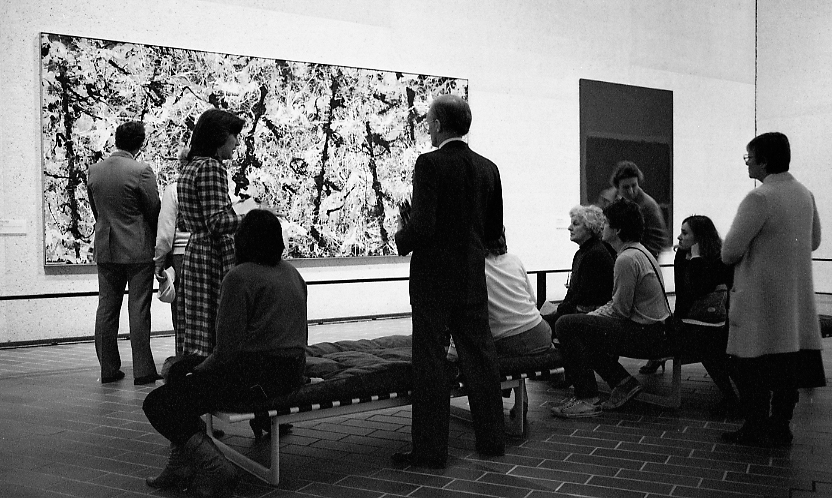

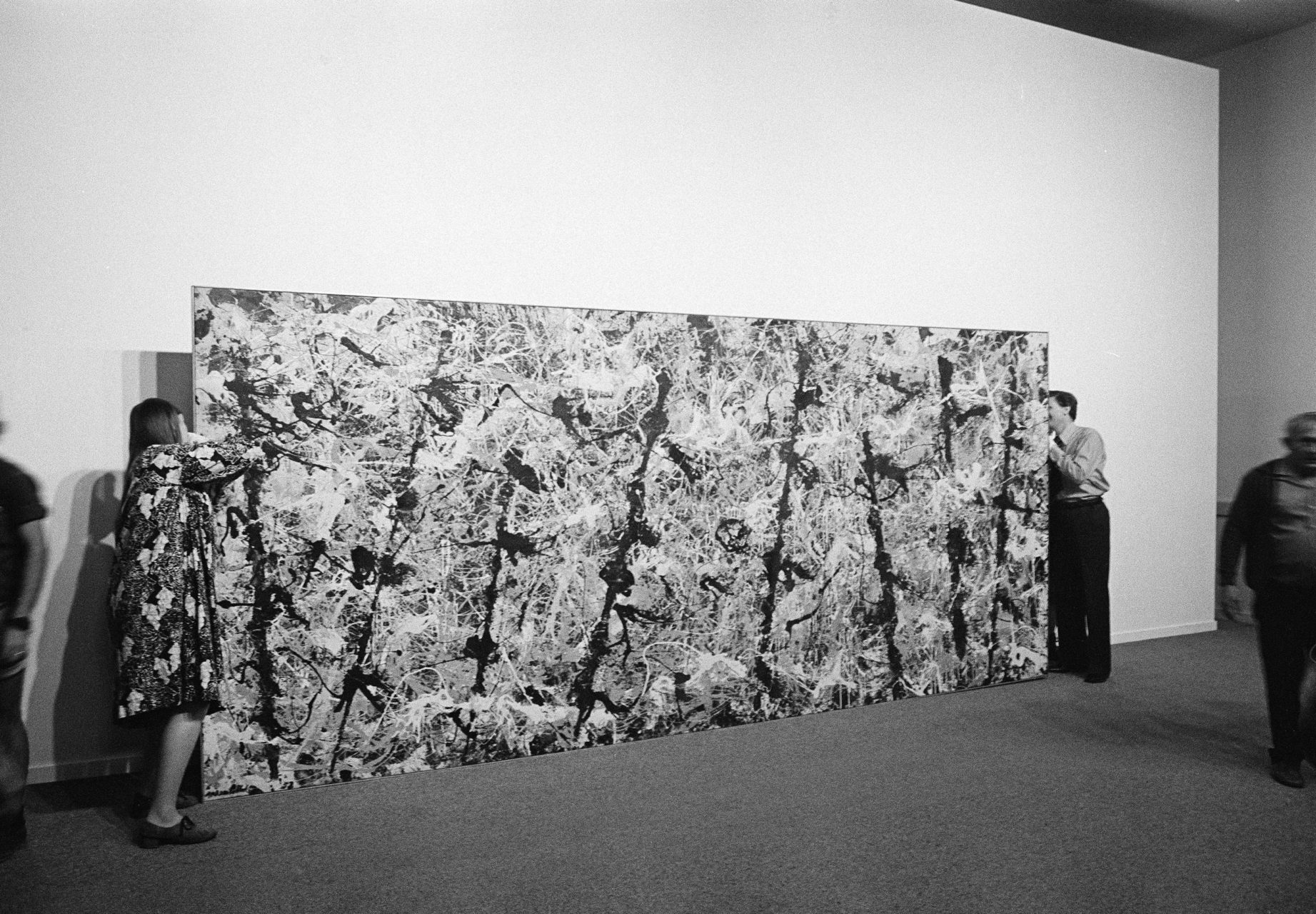

Although the context around the acquisition of Blue poles keeps changing, a quality of super-charged charisma still clings to the painting, eclipsing questions of artistic merit. Robert Hughes articulated the dilemma when, in a 1976 documentary,1 he approached his friend, the National Gallery’s director James Mollison, with a question that is yet to receive a satisfactory answer: ‘I remember a time,’ he said, standing by a massive wooden crate from which Blue poles was about to be pulled, ‘when poles was widely considered to be a painting. And now it has suffered the fate of turning into a freak show. How are you going to de-freak it?’ Mollison did his best to meet the challenge. ‘Hopefully,’ he answered, ‘by showing it with its companions, arranged on a wall with other pictures of its period, so that people become aware that it’s simply one painting among other paintings.’ It was the best possible answer. But it would prove harder than Mollison realised at the time to make the public aware of the other works he brought into the collection.

A modern nation should have a national gallery; it’s not a controversial proposition. It is only surprising that it took Australia’s federal government such a long time to build one. First proposed in 1914, the year after Canberra itself was founded, the National Gallery of Australia didn’t open until 1982, nine years after the purchase of Blue poles. Once the proposal gathered real momentum in the late 1960s, the questions of what works it should show and how it should acquire them proved vexing. No shock there. Imagine, after all, undertaking such a task today. Imagine the competing voices, the frothing accusations around issues of funding, the polemics around identity politics, the tensions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous art, the debates pitting populism against ‘elite’ or academic tastes and so on. Imagine what the politicians would have to say and through what media channels they would choose to speak. It would be mayhem.

‘Blue poles became a target, a flashpoint, a symbol of something bigger — laudable ambition or reckless stupidity, depending on how you saw it.’

Now consider that James Mollison began advising on the National Gallery’s acquisitions in 1968. Australian soldiers we in Vietnam. Jimi Hendrix was recording his third album, Electric Ladyland. The Soviets were invading Czechoslovakia. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Paris was on fire. In Australia, the strident anti-communist John Gorton had become prime minister after his predecessor, Harold Holt, disappeared into the surf late the previous year. Before his vanishing, Holt had approved and tabled in parliament Robert Menzies’s revived plan for a national gallery. That plan was the outcome of a committee of inquiry set up in 1965. Mollison, who had been director of the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery, initially served in the Prime Minister’s Department in an informal curatorial role. Gorton didn’t want Mollison as the Gallery’s first director. His favoured candidate was the American art historian and curator James Johnson Sweeney, who was already acting as a consultant to the National Capital Development Commission, the body charged with building the new gallery. Born in 1900, Sweeney had been only the second director of the Guggenheim Museum in New York, where he was involved in the final stages of the construction of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous 5th Avenue building. His influence on the building process in Canberra was massive, and it left Mollison feeling sidelined and hamstrung. But it was Mollison, in the end, who took charge of forming the collection. At first, his acquisitions were focused on Australian art, but by 1971 he had become acting director, and a new strategy for the collection had begun to take shape. Gough Whitlam came to power the next year. The Labor prime minister was urbane and well-educated. He had a sense of humour, he was in a hurry and he gave Mollison what he wanted. Whitlam agreed with Mollison, who was trained as a teacher, that the new gallery should be a site for education and edification. It should be, in essence, a ‘civilising’ project. Again, this was hardly controversial. Art can stimulate pleasure, be therapeutic, stir up political action or deliver carefully calibrated doses of bitter truth. But around the world, big publicly funded cultural institutions tend to justify themselves, and their funding, with recourse to the rhetoric of education. Whatever its limitations, the idea that art improves us — individually and collectively — is the easiest idea around which to organise, the most democratically palatable.

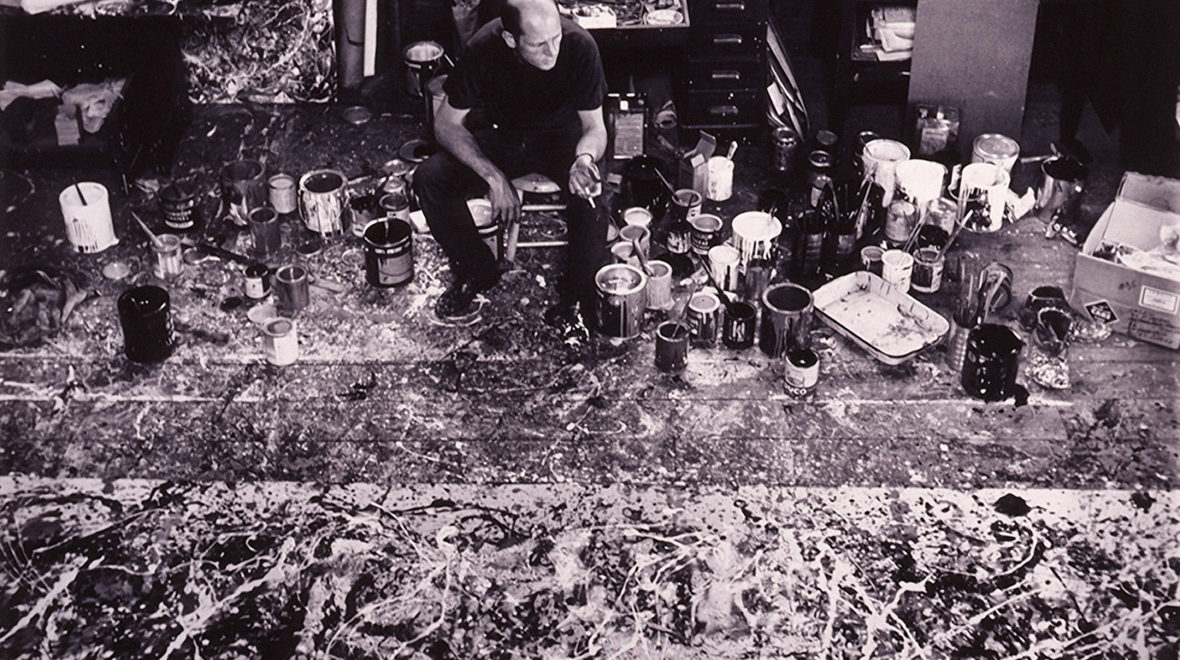

But when it came to Blue poles, there was a problem. Convincing large parts of Australia’s public that they needed to be educated about the merits of drip painting — or that being so educated would somehow improve them — was a monumental and ultimately futile task. Mollison’s attempts to make the case were earnest and sober enough. But if you were sceptical at the outset, it’s hard to see how they would persuade you. Blue poles was, Mollison told Hughes, ‘absolutely central to the abstract expressionist movement,’ a ‘contrived picture’ that was only apparently irrational, and ‘certainly the most important American picture, perhaps in all time’. Hughes himself claimed it was ‘as strictly organised as a Uccello, a formal minuet of energy’ and ‘a feat of lyric invention’. Many remained unconvinced. When Hughes asked him if he had been prepared for the criticisms provoked by the purchase of Blue poles, Mollison replied: ‘Prepared, yes, but the intensity of the attacks that were mounted on us did surprise, and they kept coming.’ Believing himself to be ‘in the job of educating people’, Mollison was dismayed, he admitted, ‘to discover that there’s one aspect of the press anyway that seems to be beyond education’. The hurt is real, but the patrician tone and lordly assumptions sound dissonant today, and the dissonance is not quite resolved by the director’s touching naivety.

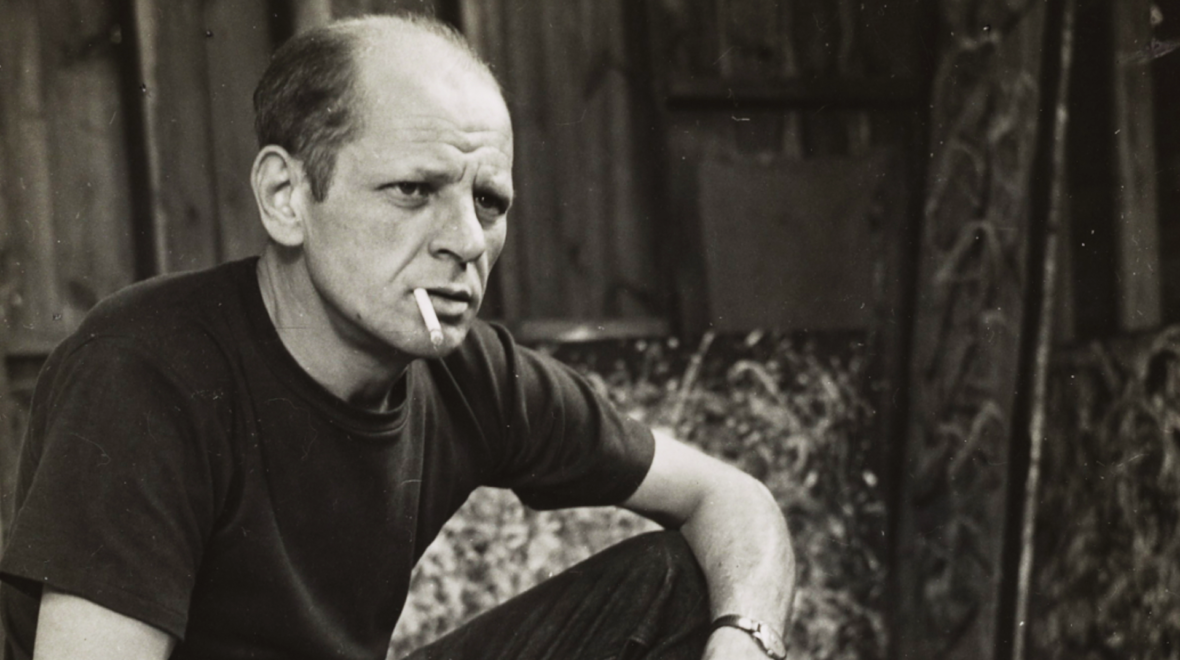

Mollison had met Hughes — a painter as well as a critic in those days — in the 1960s. Mollison worked at the time at Gallery A in Melbourne; Hughes had exhibited his work at Gallery A’s short-lived Canberra branch in 1965. (Two Hughes works ended up in the National Gallery’s collection.) The budget for acquisitions had increased steadily each year from 1967. By 1973, works of art were pouring in and public money pouring out. The scale of the project — which was almost frighteningly ambitious — had become clear. Mollison had travelled to New York in 1972. Upon his return he persuaded the board to approve the acquisitions of Willem de Kooning’s July 4th 1957, and Arshile Gorky’s Untitled 1944. Big, expensive works like these tended to get the headlines. But that year, the Gallery also acquired (beside much else) Aboriginal works from Groote Island and Tiwi designs from Melville Island in the Northern Territory.

The following year, Hughes helped Mollison facilitate the purchase of the Pollock from its then owner, Ben Heller. That year also saw the acquisitions of Constantin Brancusi’s two L’Oiseau dans l’espace (Bird in space) c 1931–36 sculptures and Andy Warhol’s Elvis 1963 as well as hundreds of other works in every imaginable style and medium. Was the whole project, asked Hughes in the first few seconds of the 1976 documentary, ‘just another mega-bucks vacuum cleaner, sucking up vicarious prestige? Will it make sense in the Australian context?’ This was the deeper challenge and it’s clear in retrospect that Mollison met it admirably.

Constantin Brancusi, L’Oiseau dans l’espace [Bird in space], c.1931-36, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1973. © Constantin Brancusi. ADAGP/Copyright Agency

It’s true that he had enormous spending power. But he also had a clear strategy. (‘It took politicians a while to realise that we were absolutely serious about what we were doing,’ he told Hughes.) Given the pressures imposed by public funding, he might plausibly have decided to focus almost exclusively on white Australian art. The modern Aboriginal art movement, which kicked off in the desert community of Papunya in 1971, was still a little-known and fledgling phenomenon. Nationalist sentiment, meanwhile, prevailed in the art world, where artists and dealers were clamouring for local patronage.

But Mollison rejected that temptation. Instead, he pursued a clear two-pronged strategy. On the one hand, he bought Australian art. He did so on such a vast scale that the acquisitions transformed both the market for Australian art and the scholarship around it. In just a few years, the Gallery spent around AUD $1.5 million, becoming the biggest single patron of Australian art. The almost cyclonic force of this collecting frenzy was a welcome stimulant. Forgotten artists, including many women, were returned to prominence. Neglected artists were given a deserving spotlight. Established artists were seen in a new light. But Mollison was also convinced that the Gallery needed to place Australian art in an international context. Heller, the collector who sold Blue poles to the Gallery, remembered something Mollison said and which he, Heller, claimed to find very persuasive. It was ‘that Australia did not want to see itself as a white bastion in a yellow world. That it wanted to see itself as part of the Pacific community.’2

‘Robert Hughes claimed [Blue poles] was ‘as strictly organised as a Uccello, a formal minuet of energy’ and ‘a feat of lyric invention’.’

Thus, Mollison focused on buying non-Australian art in three main categories. He acquired objects from the South Pacific, sub-Saharan Africa and Mesoamerica with the idea, according to Hughes, of forming ‘a small, very concentrated group — 20 or 30 objects, no more — of what Mollison calls “exemplary objects”… dating from the 5th century BC to about 1850’.

The second category, which was to produce a group of about the same size, was to be comprised of ‘major works of the seminal years of [European] modernism’, about 1850 to 1950. The third — ‘more elastic in size and more compendious in scope’, according to Hughes — was to be made up of international art since the 1950s. Since all of this was going to cost ‘quite a lot of money’, as Hughes put it, the danger was that the high prices paid for the overseas works would overshadow the Australian works. The discrepancy was inevitable since the foreign works were bought in a competitive international market, while the Australian works were purchased in a strictly local market. Mollison worried that, when the prices for the international works became public, the inevitable comparisons might reinforce a sense of cultural inferiority and lead to resentment and criticism, both of Mollison and of the international art he acquired for the Gallery.

Both things happened. The purchase of Blue poles, an abstract drip painting by an American drunk, was the nadir. Whether or not Pollock had made a compelling work of art was not really the point for Mollison’s critics. They didn’t care that the American’s breakthrough style had transformed people’s understanding of what painting could be, unleashing in the process, tremendous new possibilities for art and leading the way into new forms of abstract painting as well as into performance art, land art, dance, film and even fiction. (When asked, near the end of his life, to describe what he was trying to do in his novels, Philip Roth answered that he had tried to write in the same way that Pollock painted.3) The critics simply looked at the price and at the fact that the painting was by an American instead of an Australian and rebelled against the whole project.

Jackson Pollock, Blue poles 1952, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1973. © Pollock-Krasner Foundation. ARS/Copyright Agency

Today, the argument over whether or not the purchase of Blue poles was a good idea feels, for most people, redundant. Or rather, the debates over artistic merit and collecting policy are rendered irrelevant by the painting’s monetary value. Hardly an article is published without mention of the painting’s current valuation — somewhere in the hundreds of millions last time I checked. This fact alone wins the argument for most people. Of course it was a good idea! It doesn’t matter to them that the National Gallery will never sell Blue poles. The rising valuation proves that it was a ‘good investment’. Thus, Mollison is vindicated.

This would make some sense, I suppose, if art prices were a credible proxy for artistic merit — if the market reflected a deeper reality connected to aesthetic judgements. But the reasons for believing this are slender and getting more so. Seen clearly, the high-end art market is the result of very small numbers of obscenely wealthy individuals (and a few sovereign investment funds) fighting over limited numbers of art works by artists with already established reputations. Although originating in judgements of merit, the economic mechanism taking art prices to today’s crazy levels has essentially been uncoupled from aesthetics. It is self-propelling. So the astronomical prices really prove nothing.

In any case, the only antidote to the prevailing fascination with the monetary valuation of Blue poles is to see the work in a context where it is not for sale — a public gallery — and to surround it, as Mollison said he wanted to do from the beginning, with other works of art.

This story was first published in The Annual 2023.

- Unless other mentioned, all quotations from Robert Hughes, ‘The collection’, ABC documentary, 1976 (published online 2021), National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, viewed 29 June 2023 https://nga.gov.au/on-demand/the-collection-with-robert-hughes/

- Tom McIlroy, ‘The Man Who Sold Jackson Pollocks’ Blue Poles to Australia’, Financial Review, 18 October 2019, https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/the-man-who-sold-jackson-pollock-s-blue-poles-to-australia-20191010-p52zl5

- Steven Valentino, ‘The Many Literary Lives of Philip Roth’, The New Yorker Radio Hour, 21 July 2018, https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/tnyradiohour/segments/many-literary-lives-philip-roth

More