19

12

At the Watkins Ranch, Cody, Wyoming, USA, on 28 January 1912, Paul Jackson Pollock was born to LeRoy (Roy) Pollock (1877–1933) and Stella May McClure Pollock (1875–1958). He was the youngest in a family of five brothers: Charles Cecil (1902–1988), Marvin Jay (1904–1986), Frank Leslie (1907–1994), and Sanford (Sande) LeRoy (1909–1963). At the end of the year the Pollock family moved to a fruit-growing community south of San Diego.

13

The Pollocks moved to Phoenix, Arizona where Roy worked their small farm while Stella kept house and encouraged her sons’ artistic inclinations. Charles began oil painting lessons. From an early age Jackson would always say, ‘I want to be an artist like brother Charles’.1

17

Struggling financially, the Pollocks moved to a large timber house on a stone-fruit orchard in Chico, in the central valley of Northern California, where Jackson started school.

18

In September, Jackson enrolled at the nearby weatherboard Sacramento Avenue School that Sande attended. ‘Sande told me that he didn’t learn much in school and Jack didn’t learn anything.’2

19

The Pollocks moved to Janesville, California, 190 kilometres north-east of Chico, went further into debt and bought a hotel, the Diamond Mountain Inn, with 55 hectares of land attached.

20

Jackson had his first contact with indigenous Wadatkut culture and mysticism through their Indian housekeeper, Nora Jack. Roy and Stella’s marriage was in tatters. Roy left to work away from home with State and Federal survey teams, but stayed in contact with letters, money, and rare, brief visits.

22

Charles moved to Los Angeles and began classes at the Otis Art Institute. He sent copies of The Dial, a monthly periodical of fiction, poetry, book reviews, art criticism and black-and-white reproductions of fine art to the boys now living in Orland, California, giving Sande and Jackson their first exposure to modern art. Financial strain forced Stella to sell the farm and re-join her husband in Arizona.

23

Roy had a surveying job in Tonto National Forest and the family drove to Phoenix to join him. Jackson enrolled in sixth grade at Monroe Elementary School in Phoenix.

Frank and Sande were truanting and drinking and eventually left school. ‘Sande drank, I drank, Charles drank, we all drank.’3

24

All the family possessions were destroyed in a warehouse fire in Chico. Stella took Frank, Sande, and Jackson to Riverside California, a prosperous and cultured town about 95 kilometres east of Los Angeles, and took in boarders in their large house to support them. Sande and Jackson were undisciplined but almost in separable.

They played together, ate together, slept together. But the taking care of the other was by Sande of Jack; it was never the other way around. Jack never could take care of himself.4

26

After several years in Los Angeles studying at Otis Art Institute, Charles moved to New York, where he registered as a student of Thomas Hart Benton, the American Regionalist painter, at the Art Students League.

Jackson enrolled in Manual Training School on Chestnut Street in September. When Sande began dating, the brothers’ relationship changed. ‘I can’t remember Jack ever dating.’5

27

Jackson joined Sande at Riverside High School and although their relationship was rekindled to some extent, it was never the same. Jackson was relatively isolated and became a regular drinker. To avoid organised sport, he joined the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC), but his timidity was mitigated by alcohol, and he was thrown out for punching a student officer during a parade drill.

28

In the ensuing months Jackson battled with study and his emotional stability until he dropped out of high school.

Jackson moved with Stella to south Los Angeles, and began classes at Manual Arts High School. Jackson found abstract art and the writings of mystical thinkers, such as Krishnamurti and Rudolf Steiner the founder of Theosophy, through the art master Frederick John de St. Vrain Schwankovsky.

29

Jackson was expelled twice from Manual Arts High School over the next two years for disciplinary problems.

At school he was a rebel, couldn’t conform … He made a big effort … trying to be conventional, you know, but just couldn’t make the grade. Not everybody was nice to Jackson, but he had a special charm. I always thought in his own mind he was sort of an orphan.6

Jackson began reading about avant-garde artists of the day such as Diego Rivera, the Mexican muralist, in Creative Art magazine.

30

With the help of Schwankovsky who promised close supervision, Jackson agreed to forgo graduation and attend Manual Arts on a part-time basis.

Charles and Frank returned to Los Angeles for the summer. Jackson and Charles went to Frary Hall at Pomona College in Claremont, to see the Mexican muralist Jose Clemente Orozco’s Prometheus fresco.

Jackson later joined Charles and Frank in New York City where he took sculpture classes at Greenwich House, and then enrolled in Thomas Hart Benton’s class at the Art Students League.

31

Unknown by other students, he earned special attention and private tutoring from Benton. ‘His mind was absolutely incapable of logical sequences. He couldn’t be taught anything.’7

32

Jackson’s drinking and growing depression concerned his family, so Frank and his wife Marie took him to Los Angeles. When Jackson returned to New York, he moved into the small apartment of Charles and his wife Elizabeth at 46 Carmine Street, which both men used as studio space. Jackson exhibited his work on a sidewalk at the second annual Washington Square Outdoor show.8

33

At the Art Students League, Jackson studied life drawing, painting and clay-modelling and studied stone carving at Greenwich House Annex.

Roy Pollock died on March 6 after a three-month fight against malignant endocarditis, a bacteria infection of the valves of his heart.

Jackson, Charles and Elizabeth rented a floor in the building at 46 East 8th Street for $35 a month.

Jackson spent time watching Diego Rivera paint his controversial mural in the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center.

35

Jackson painted an explicit mural ‘à l a Orozco’ on the walls of his studio, and in February, showed Threshers at the Brooklyn Museum in The Eighth Exhibition of Watercolors, Pastels, and Drawings by American and French Artists.

Benton left for Missouri to take a position as the Director of the Kansas City Art Institute. Jackson and Sande joined the Federal Arts Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Sande changed his last name to his father’s birth name, McCoy, to avoid the authorities detecting two members of the same family collecting two wages from the agency.

36

Still working for the Federal Arts Project, Jackson’s proposal for a mural commission was unsuccessful.

Siqueiros established a ‘Laboratory of Modern Techniques in Art’ in his loft at 5 West 14th Street, and Jackson and Sande participated in the workshop, helping to prepare posters, banners, and a giant float for the May Day celebration. Siqueiros experimented with non-traditional materials such as enamel paint, and with unconventional techniques of paint application: airbrushing, pouring, and dripping, which Jackson subsequently adapted to his own work.

Sande, Philip Goldstein (later Guston), Reginald Wilson and Bernie Steffen accompanied Jackson to see Orozco ‘s mural The Epic of American Civilization, in the Baker Library, Dartmouth College, in Hanover, New Hampshire. By winter he began drawing skeletal half-humans, beasts, and skulls from Orozco’s influence.

Over the winter holiday season, the exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism was on view at The Museum of Modern Art, and Jackson met his future wife, Lenore (Lee) Krasner, at a Christmas party.

37

Because of his continued state of depression and drinking binges, Sande insisted that Jackson attend a Jungian analyst, Cary Baynes, for psychiatric treatment.

Becky Tarwater refused Jackson’s marriage proposal.

Sande annexed the front part of the Houston Street apartment for Jackson to use as a studio.

38

The psychiatric treatment was unsuccessful, the drinking binges continued, and his work dwindled to very little. Jackson finally lost his job with the Federal Arts Project because of his frequent delinquency. He signed himself into the Westchester Division of New York Hospital as a charity patient. Here he had six months of Freudian analysis and worked in the metal workshop making bowls and copper plaques.

By November he had resumed working for the easel division of the WPA project.

39

Jackson had a second breakdown and was treated for 18 months by another Jungian psychoanalyst, Dr Joseph Henderson, who used his drawings as points of departure for the therapy.

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, with preparatory sketches, was shown at the Valentine Gallery on 57th Street where it was exhibited by the Artists’ Congress to help raise funds for refugees from the Spanish Civil War. Jackson was fascinated by animal imagery and revisited it repeatedly, sometimes sketching it.

Jackson encountered art critic and artist John Graham who saw genius in his work, played down the necessity for technical skill, and espoused the expression of the unconscious in art.

40

Pollock began to paint with a new confidence, attracting admirers of both his work and himself.

When almost simultaneously his time with the government scheme finished and his close friend, Helen Marot died, he reverted to his earlier destructive habits of drinking rather than painting. Dr Henderson, who had failed to help him, moved to San Francisco leaving his therapy to Dr Violet Staub de Laszlo, whom he visited twice a week for a year.

41

The exhibition Indian Art of the United States, a subject that had fascinated him from childhood, was shown at The Museum of Modern Art, and featured Navajo artists executing sand paintings on the gallery floor. In the build-up to US entry into the Second World War, Jackson was excused from compulsory military service on the grounds of his mental health.

42

Pollock’s Birth c.1941 appeared with works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, Andre Derain, and American artists including Stuart Davis and Walt Kuhn and Lee Krasner in American and French Paintings, organised by John Graham, at McMillen Inc., at 148 East 55th Street. lmpressed by his work, Krasner was pivotal in the turning point in Pollock’s life. She introduced him to the influential German emigre artist Hans Hofmann and members of his circle, such as Mercedes Carles and Herbert Matter.

Through Matter, Pollock came to know James Johnson Sweeney, who introduced his work to wealthy art collector Peggy Guggenheim.

When Sande moved his family from their shared 8th Street apartment to Deep River, Connecticut, Krasner moved in. Pollock took part in a failed automatist artists’ workshop with artists such as Motherwell and Matta.

At the end of the year Pollock showed The Flame c.1934–38 in Artists for Victory at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

43

Pollock first exhibited at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery, showing the lost work Collage in an international collage exhibition.

Pollock worked as a custodian of paintings at The Museum of Non-Objective Painting, later renamed the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

He participated in the Spring Salon for Young Artists at Art of This Century. Mondrian predicted great success for Pollock and claimed the artist’s Stenographic Figure (c 1942) as the most noteworthy work he had seen in the country.

After visiting Pollock’s studio, Guggenheim offered him a solo show, his first and the first of an American artist at the gallery, in November 1943, signing a 12-month contract of $150 monthly advance to paint full-time.

Guggenheim commissioned a mural to be painted on the wall of the entrance hall of her town house but, realising she would lose it if she moved, had him paint it on canvas. Pollock removed a wall in his East 8th Street apartment to fit the twenty-foot-long canvas that he finished at the end of the year.

44

Robert Motherwell interviewed Pollock for the February issue of Arts & Architecture. In it he espoused the qualities of Native American art, the universality of modern painting problems, and the stimulation provided by the demands of living in New York.

The She-Wolf was acquired by The Museum of Modern Art for $650.

Pollock began printmaking at Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17, across from his apartment in New York.

45

Pollock’s second solo exhibition at Art of This Century had thirteen paintings as well as gouaches and drawings. In The Nation, critic Clement Greenberg’s review hailed Pollock’s work and proclaimed the artist as the leading painter of his peer group.

Pollock renewed his contract with Guggenheim who doubled his monthly payment in exchange for every painting that he produced in a year, except for one chosen by him.

Krasner and Pollock married on 25 October at the Marble Collegiate Church on Fifth Avenue, and moved into a farmhouse at 830 Fireplace Road, The Springs, East Hampton, Long Island. His family came to visit at Thanksgiving.

Painting ceased during the next few months while they tried to fix up the house that had no hot water, bathroom or heating.

46

When Pollock resumed painting, an upstairs bedroom became a temporary studio. At his third solo exhibition at Art of This Century, he exhibited eleven oil paintings and eight temperas, to critical acclaim.

Pollock moved the barn to the side of the property so that it no longer obstructed the backyard view of Accabonac Creek. It became his studio and Krasner used the upstairs bedroom as her studio.

In December he exhibited the 1943–45 canvas Two at the Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting – the ‘Whitney Annual’ – at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

47

At Pollock’s fourth solo exhibition at Art of This Century, the 16 paintings fell into two discrete groups. The Accabonac Creek Series consisted of works painted in the upstairs bedroom before summer 1946, and the Sounds in the Grass Series was of paintings finished in the barn studio. Mural was shown there, and again in the exhibition Large Scale Modem Paintings at The Museum of Modern Art.

When Guggenheim decided to return to Europe, the dealer Betty Parsons agreed to show his work.

Clement Greenberg defined Pollock as ‘The most powerful painter in contemporary America and the only one who promises to be a major one is a Gothic, morbid and extreme disciple of Picasso’s Cubism and Miro’s post-Cubism, tinctured also with Kandinsky and Surrealist inspiration. His name is Jackson Pollock’.9

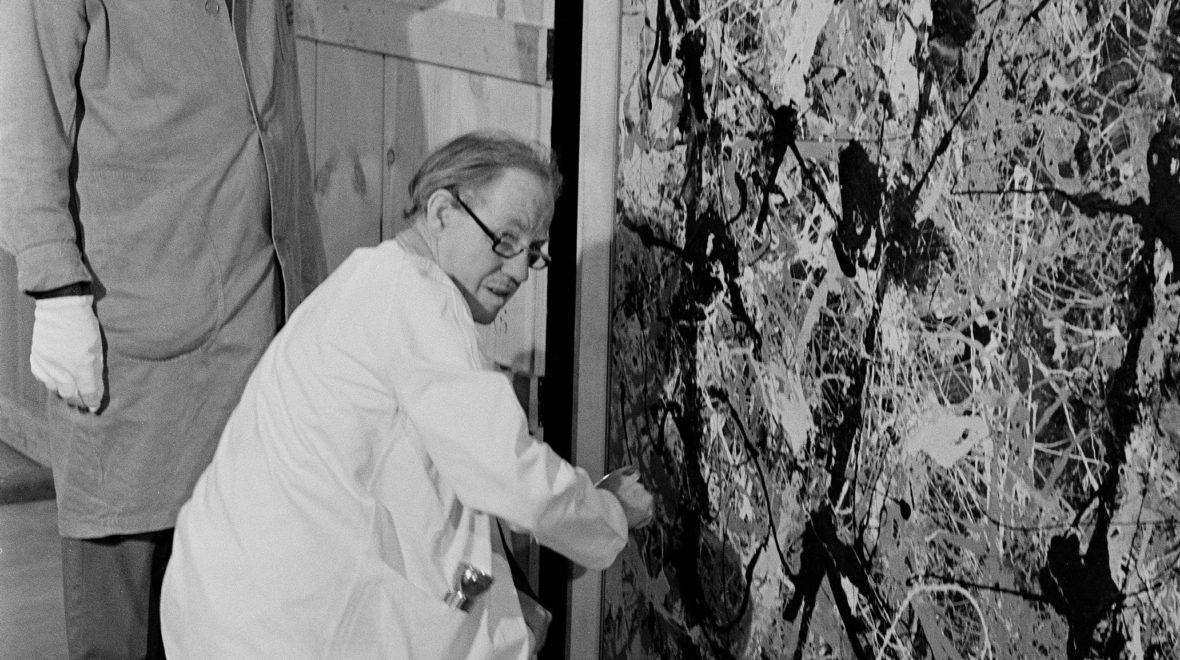

His canvases were getting ever larger so that his painting technique changed to accommodate them. Pollock explained why he used his floor technique: ‘On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more a part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting … When I am in my painting, I’m not aware of what I am doing. It is only after a sort of “get acquainted” period that I see what I have been about’.10

48

His first exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery at 15 East 57th Street included seventeen paintings. Only two sold.

Eyes in the Heat, The Moon Woman, and Two were three of six works shown as part of the Peggy Guggenheim collection, along with another four, at the XXIV Venice Biennale that later travelled to Florence and Rome.

After an accident, Pollock met Dr. Edwin Heller, a general practitioner who had moved to East Hampton, who claimed to have a cure for alcoholism. Under Heller’s care, he stopped drinking.

49

Pollock began his numbering system of identifying paintings in earnest, and at his second Betty Parsons show displayed 26 works that were painted in 1948.

Pollock remained sober and the home was harmonious.

He signed another contract with Betty Parsons that was valid until 1 January 1952. Pollock met fellow painter Alfonso Ossorio.

Dorothy Seiberling published: ‘Jackson Pollock: Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?’ in Life magazine accompanied by photographs of Pollock at work and standing in front of Summertime: Number 9A, 1948.

Pollock’s third solo show at the Betty Parsons Gallery included thirty-five works.

50

The Pollocks were guests of Ossorio at his apartment in New York for part of the winter. Number 1A, 1948 was acquired by The Museum of Modern Art.

At the US Pavilion at the XXV Venice Biennale Pollock showed three paintings: Number I A, 1948; Number 12, 1949; and Number 23, 1949.

Pollock passed the summer in collaboration with Tony Smith and Alfonso Ossorio on the design and construction of a Long Island Catholic church of which Pollock’s part was a series of paintings, however, the project never came to fruition.

Interviewed for radio by William Wright, Pollock said, ‘Most of the paint I use is a liquid, flowing kind of paint. The brushes I use are used more as sticks rather than brushes – the brush doesn’t touch the surface of the canvas, it’s just above … I don’t use the accident – ’cause I deny the accident … I do have a general notion of what I’m about and what the results will be … the result is the thing and it doesn’t make much difference how the paint is put on as long as something has been said. Technique is just a means of arriving at a statement.”11

Pollock had a solo exhibition at the Museo Correr, Venice, of twenty paintings, two gouaches, and one drawing from Guggenheim’s collection.

The Italian critic Bruno Alfieri reviewed the exhibition, and described Pollock’s work as ‘chaos’. Pollock responded with a telegram which was published in Time magazine in December, part of which read: NO CHAOS DAMN IT.12

His fourth solo show at the Betty Parsons Gallery included some of his best work ever: including Lavender Mist; Number 27; Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, 1950; One: Number 31; and Number 32.

Pollock agreed to let the photographer Hans Namuth photograph him while he painted. Over several visits to the studio, Namuth took about 200 photographs of Pollock at work on One: Number 37, 1950 and Autumn Rhythm. The evening Namuth finished filming Pollock outside at work on a painting on glass, Number 29, 1950, in the cold November weather, Pollock lost his battle with alcohol, ending two years of sobriety.

It was a bloody cold day, a mean wind out of the northwest … Hans and Jackson came in literally blue – you know, frozen – and I saw Jackson go across to the sink, reach down, and pull out a bottle of whiskey. He filled two water glasses and said to Hans, who had never seen him in action, ‘This is the first drink I’ve had in two years. Dammit, we need it!’13

51

Pollock’s fourth solo exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery was chosen by Artnews as one of the three best exhibitions of 1950.

In spite of his success Pollock was troubled, writing to his friend Ossorio, ‘I found New York terribly depressing after my show – and nearly impossible – but am coming out of it now’.14

Number 1A, 1948 is included in the exhibition Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America at The Museum of Modern Art.

‘Pollock paints a picture’, an article by Robert Goodnough, was accompanied by five Namuth photographs showing Pollock working on Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, 1950.

Krasner had her first solo exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery in October.

Pollock experimented with drawing on canvas in black paint from which some of his early figurative images began emerging. He presented many of these black paintings at his fifth solo show at the Betty Parsons Gallery where he showed 21 paintings.

52

He exhibited eight paintings in The Museum of Modern Art 15 Americans exhibition including; Number 2, 1949; Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, 1950; and Number 22, 1951.

When his contract expired with Betty Parsons he moved to the Sidney Janis Gallery, just across the hall at 15 East 57th Street.

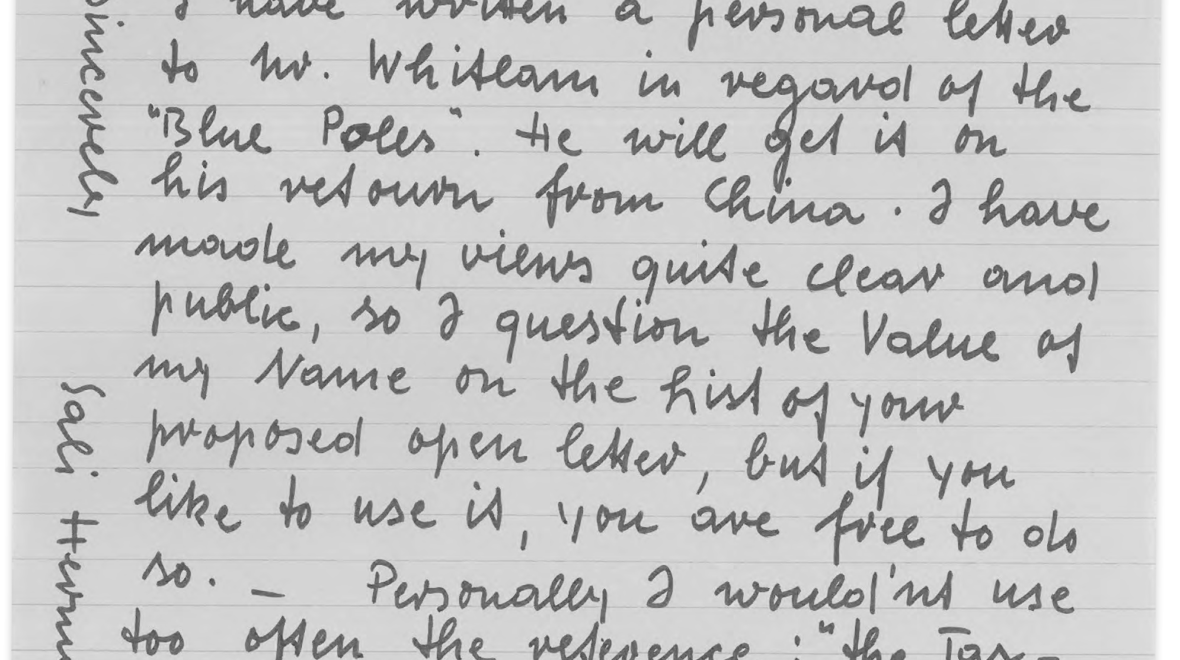

Among the paintings produced this year was Blue poles, Number 11, 1952. The canvas, which Pollock began with Tony Smith early in the year, was worked on over several months. As Lee Krasner explained, ‘A painting like Blue poles he reentered many, many times, and just kept saying, “This won’t come through” … When he got hung up in something, like Blue poles, where he did get hung up, it took quite a long time. This went on beyond weeks. He might just walk away from it for a stretch of time, and then come back, reenter’.15

At his first solo exhibition with Sidney Janis in November, he showed 12 paintings from 1952, including Blue poles. Only one painting, Convergence: Number 10, 1952 was sold from the exhibition (to Nelson Rockefeller), but reviews were complimentary. Robert Goodnough wrote:

The very large paintings … make the gallery seethe with energy, yet a gentleness pervades that settles the pictures back to stillness… One feels a struggle from the impassioned beginning to the final concise declaration … When there is too much activity, strong bars of color act like bold guards to hold things back, as in Blue poles: Number 11.16

53

Pollock was drinking steadily again and his marriage was strained. He was despondent. His work slowed and any accolades were centred on Pollock’s work of the previous year.

Pollock and Krasner invited his now elderly mother, Stella, to live with them at The Springs. It didn’t last and Jackson became more depressed.

He painted Portrait and a Dream, 1953, and The Deep, 1953, the latter in homage to the work of Clyfford Still who had also joined the Janis Gallery.

To the Janis Gallery’s 1953 exhibitions 5th Anniversary Exhibition and 9 American Painters, Pollock sent works from 1952 including Blue poles.

In a letter to Sidney Janis, Pollock writes: ‘ I think No. 11 –1952 (Blue poles) size 83 x 192 a good painting for the 9 American painters show. I have it here at the house and will send it in via Home Sweet Home movers, unstretched, the last week in Dec.’17 Janis recalls the cavalier way in which Pollock handled his work: ‘At the conclusion of the show [in 1953] Pollock, slightly stoned, helped us dismantle the show. He laid Blue poles on the floor and he ripped the canvas off the stretcher, the staples machine-gunned out of it and into the wall. The work was put on a roll, and stood in our back hall at the fire exit for a year or so … it was finally sold to Mr. Olsen [in 1955 for US$ 6,000]’.18

54

Pollock’s second solo exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery in February, originally scheduled for November, 1953, comprised 10 paintings, all from 1953, including The Deep, Easter and The Totem, and Portrait and a Dream.

Pollock became more isolated from his circle of friends. Krasner had resumed painting and was preparing a show. In mid-year Pollock broke his ankle and missed the opening. He broke the same one eight months later.

Late in the year Stella Pollock had three mild heart attacks and Jackson paid her several visits. He sold Ocean Greyness to the Guggenheim Museum and sent money to his family.

55

More depressed than ever, Pollock returns to therapy in New York City with Dr Ralph Klein. The regular city visits began to include regular drinking sessions.

With his marriage in ever worsening shape, Pollock threatened to move to Paris, and obtained a passport.

Krasner’s solo exhibition of large collage paintings opened at the Stable Gallery in September. As Krasner emerged more as an artist, Pollock receded more into a creative void.

Without a complement of recent paintings, his third solo exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery became a survey exhibition, 15 Years of Jackson Pollock.

56

Pollock had not painted for more than a year and yet remained adamant of his place in contemporary art, rejecting labels and descriptions of critics. He said of his work in an interview, ‘it’s certainly not “non objective”, and not “non-representational” either. I’m very representational some of the time, and a little all of the time. But when you’re painting out of your unconscious, figures are bound to emerge.’19

When in July, Krasner left for a trip to Europe, their relationship ever more strained, he stayed behind at The Springs. During Krasner’s absence Pollock’s mistress, Ruth Kligman, a young New York artist, moved in with him, but his drinking and contrariness made the arrangement short-lived. He missed his wife and sent red roses to Paris. She sent postcards in return.

A week later Kligman returned for the weekend with a friend, Edith Metzger.

On 11 August, driving drunk in his VB Oldsmobile convertible at 10:15p.m. with the two women, Pollock crashed the car on Fireplace Road and was killed along with Metzger. Kligman survived.

Lee Krasner returned home immediately for Pollock’s funeral at The Springs Chapel.

Pollock’s mid-career exhibition organised by The Museum of Modern Art was mounted as a retrospective with 35 paintings and nine watercolours and drawings from the period 1938–56 and opened four months after his death.

MYRA MCINTYRE was a curatorial assistant in International Art at the National Gallery of Australia.

References:

- Stella Pollock to a reporter in 1957, in Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, Jackson Pollock: An American saga, New York: Clarkson N Potter, 1989, p. 64.

- Frank Pollock in, Jeffrey Potter, To A Violent Grave: An oral biography of Jackson Pollock, New York: G. P. Putnam ‘s Sons, 1985, p. 25.

- Ibid., p. 27.

- Ibid., p. 22.

- Robert Cooter in Naifeh and Smith, p. 11 4.

- Manuel Tolegian in Potter, p. 28.

- Thomas Hart Benton in Naifeh and Smith, p. 206.

- Naifeh and Smith, p. 207

- Clement Greenberg, ‘The present prospects of American painting and sculpture’, Horizon, London, 16, no. 93–94, October 1947, pp. 25–26.

- Jackson Pollock, ‘My Painting’, Possibilities, New York, no. 1, Winter 1947–48, pp. 79, reprinted in Pepe Karmel (ed.), Jackson Pollock: Interviews , Articles and Reviews, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1999, p. 17–18.

- Jackson Pollock, interview with William Wright, in Francis V. O’Connor and Eugene V. Thaw, Jackson Pollock: A Catalogue Raisonne of Paintings, Drawings, and Other Works New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1978, vol. 4, pp. 248–51, doc. 87.

- See ‘Letter to the Editor’, Time, 56, no. 24, 11 December, 1950, p. 10.

- Peter Blake in Potter, p. 131.

- Letter to Alfonso Ossorio, January 6, 1951 Reprinted in O’Connor and Thaw, Jackson Pollock: A Catalogue Raisonne, vol 4, p. 257, doc. 93.

- Lee Krasner in Barbara Rose ‘Jackson Pollock at Work: An interview with Lee Krasner’, Partisan Review, 47, no. 1, 1980, pp. 82–92, p. 89.

- R[obert] G[oodnough], Artnews, 51, no. 8, December 1952, p. 42.

- Jackson Pollock, letter to Sidney Janis, undated, reprinted in O’Connor and Thaw, vol. 4, p. 271.

- Sidney Janis, quoted in Les Levine, ‘A portrait of Sidney Janis on the occasion of his 25th anniversary as an art dealer’, Arts Magazine, 48, no. 2, November 1973 p. 52.

- Jackson Pollock in Selden Rodman, Conversations with Artists, New York: The Devin-Adair Co., 1957, pp. 76–87, quoted in Kirk Varnedoe with Pepe Karmel, Jackson Pollock, New York: Museum of Mod ern Art, 1998, p. 328.

More