Jackson Pollock’s Blue poles hanging in Ben Heller’s apartment in New York’s Central Park West in the early 1970s

The Heller family visited Blue poles at the National Gallery of Australia in 2015

As the daughter of the late New York art collector Ben Heller, Patti Adler grew up with Blue poles in the living room. Ahead of a visit to Canberra in 2015, Patti and her husband Peter spoke with the National Gallery’s Eric Meredith about what it was like growing up surrounded by masterpieces of Abstract Expressionism at home.

Eric Meredith

Patti, you’re the daughter of art collector Ben Heller, who previously owned Blue poles 1952. And you lived with the work for many years as a child through to adulthood.

Patti Adler

Yes, he [Ben] purchased the piece in 1957, so I was six, and sold it in 1973.

Eric Meredith

The work toured pretty extensively during the 1950s and 1960s.

Patti Adler

It was in and out of the apartment a lot. It was very exciting every time it left because it was too big to fit through the front door. We lived in an apartment building [in New York], on the tenth floor, so they basically took one wall of this historic building and made a gigantic window. They would take the entire window out, put Blue poles in this big box and block off the street – Central Park West! – and they would have seven guys out there, with these ropes and pullies, taking it out of the window and lowering it down to street level and putting it in the van.

Eric Meredith

We have some great pictures of that actually.

Patti Adler

The Seven Santini Brothers.

Eric Meredith

So, what was it like the last time it went through that window in 1974.

Patti Adler

Oh, we were all really sad leading up to that. We assembled in the living room the day before it left, and we, as a family, had a chance to talk about it. Everybody went around in a circle and said their feelings about it. Things have come and gone but, for some reason, this was the biggest loss we all experienced.

Peter Adler

As an outsider who was there, it seemed almost like losing a pet.

Patti Adler

There was a lot of crying.

Eric Meredith

And now, after seeing it again? It was an emotional reunion. Has it stirred particular memories?

Patti Adler

It really is impressive. I’m blown away by it. The frenzy, power and intensity of Blue poles, it’s spectacular, and it’s really done well to overcome its detractors. Blue poles was more than an object to us. It was so special. And I really hope our visit has added a new dimension to the painting – showing the world the great value and love that it was raised in our family. It is a piece of our history, a piece of my family and a piece of me.

Eric Meredith

And a piece of Australia’s history, too. Although not always so loved here. When the National Gallery purchased Blue poles in 1973, it caused quite a controversy, a lot of it was whipped up by the media. It was a scandal: the amount of money that was spent, Pollock’s drinking habits were brought into question, allegations of Tony Smith and Barnett Newman contributing to the work. How much of all that were you aware of?

Peter Adler

Very little. All of the hoopla in America was that it was the most ever paid [US$2 million] for an American painting. It was a record that stayed in the Guinness Book of World Records for ten years, so it was quite ahead of its time in terms of its price. Obviously, the Australian government got its money’s worth. But we were not aware of any of the controversy in Australia.

Patti Adler

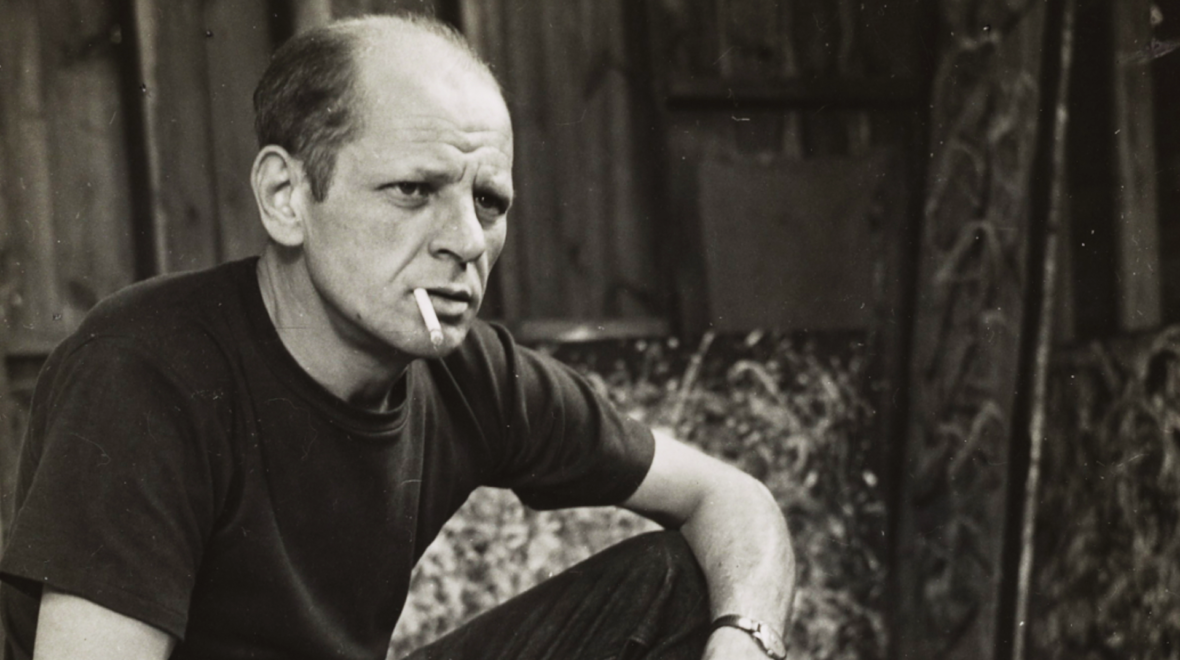

Jackson Pollock was a very, very well-known, very well-respected painter in the United States, so we had long since passed the time where people were saying, ‘Any kindergartener could do this’. ‘Jack the Ripper’, all that kind of stuff, was long gone. He was well established as the leader of the Abstract Expressionism movement.

Eric Meredith

But the main controversy in America was just the US$2 million?

Peter Adler

I would say its competitors – of his masterpieces – Echo 1951 and One 1950, hang in the Museum of Modern Art, so, I guess, you could call it controversy that it was going out of America, among the art world. Whereas, Patti’s dad felt it was very important that as many people get to see it as possible. And one of the things he wanted to say [to the National Gallery] was that he’s so happy the way you’ve handled it, and that you’re sending it to London [for the exhibition Abstract Expressionism at the Royal Academy of Arts in September 2016], and it’s his kind of vision coming true.

Patti Adler

He was very involved with this art movement from its early years, and there was a struggle among these American artists to gain recognition. Even in America, the European painters were getting all the attention and prestige. So, he worked very hard with the dealers and the painters and the museums to try to establish Abstract Expressionism as an important movement. It was very, very important to him that these major works land in major museums.

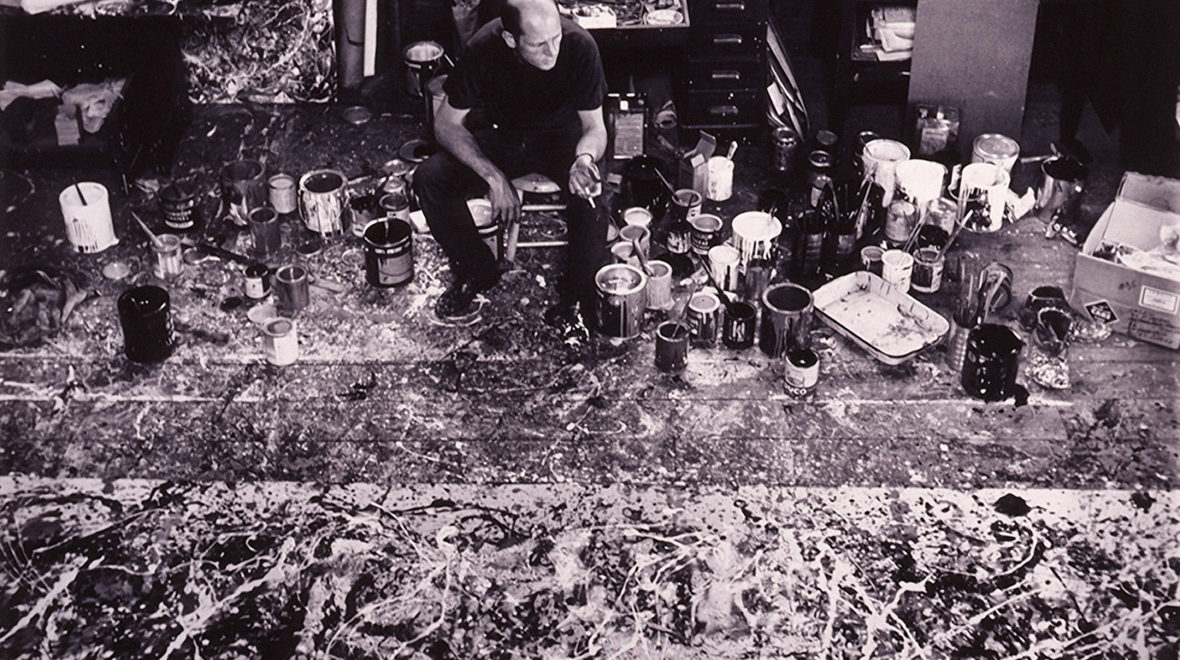

Ben Heller’s New York apartment was full of incredible works of art

Eric Meredith

You mentioned One, which MoMA has now, and that also caused a bit of controversy when your father bought it. Not only was it your father’s first Pollock but also the most money spent on one of the artist’s at that time and the largest to go into private hands.

Patti Adler

It was. He went down to Pollock’s studio when he first met him and spent some time with him. He went down one day and then he went every day all the rest of the summer. They talked a lot about music and art and he asked if he could buy it. Jackson said he would sell it – I don’t think he’d ever sold a really large drip painting before; I think it was the first he ever sold. He asked for $8000, so my father said, ‘Can I buy it on an instalment plan?’ He gave him four years to buy it. He [Ben] was twenty-eight years old. His parents thought he was crazy.

Eric Meredith

I can imagine. He has said the decision to buy One was made by him, Pollock, Lee Krasner and your mother, Judy Heller.

Patti Adler

No. Well, he went to Lee and he said, ‘Lee, do you think he would sell me this painting?’, and she said, ‘If it were me, I wouldn’t but, talk to Jackson, maybe he will’. But, together, Lee, my father and Jackson decided on the name for it. They were sitting around one evening after dinner talking about things and the painting, and Jackson said that he felt really relaxed and at one with nature when painting it, so they all decided that it should be called One – not the number ‘one’ but ‘at one’, in harmony. It’s very different to the intensity of Blue poles.

Eric Meredith

Yes, he talks about it in a MoMA interview of 18 April 2001. Was there ever a time you were involved in decisions on purchasing art?

Patti Adler

I used my babysitting money to buy something from Leo Castelli – my first work of art. And, when I was young, my dad said to my brother, sister and me, ‘I’d like to start you on your first art collection, so here’s a dozen pieces that I’ve paid $1000 or less, and you can each pick one’. I was maybe twelve. My sister took some sculpture of a dog and my brother took something, I forget what. I was the oldest and I was really enamoured with my father. I wanted to grow up and be just like him. I said to myself, ‘These are the things that he is collecting’, and I had already bought my first [Roy] Lichtenstein with my babysitting money, so I picked this piece by Robert Rauschenberg. I hauled it all over to college, to graduate school, lived with it, hung it on the wall. Long past when my father had sold all of his, I still had it.

Almost ten years ago, my husband and I were building a home in Hawaii, so we said, ‘Let’s sell the Rauschenberg’. That was also very sad for us because we’d had it for forty-something years. It was a piece of our lives. We put it to auction at Christie’s, and I listened on the phone from my office in Boulder, Colorado. My parents were there on the cell phone, listening to the auctioneer selling this painting, which had been estimated to bring in maybe US$400,000 to US$600,000. I listened as the auction went on: 400, 450, 500, 550, 600, 650, dot, dot, dot, dot, dot, dot, until it finally sold for a million and a quarter. All the people sitting around my father, they said, ‘Congratulations to your daughter. It’s wonderful. How much did she pay for it?’ He says, ‘Well, she didn’t pay anything. She got it from me’. And they said, ‘Well, what did you pay for it?’, and he said, ‘$400’.

Eric Meredith

Quite some time ago, though. You obviously had a good eye at the beginning.

Patti Adler

I guess so.

Eric Meredith

And does art still play a role in your life? Do you collect still?

Patti Adler

We do. We have some Perle Fines, some Miriam Shapiros from the East Hampton years. We had a Newman we sold around the same time as the Rauschenberg. But we’re retired now, so we needed to liquidate our assets so that we could afford to travel to Australia.

Eric Meredith

And come visit Blue poles.

Patti Adler

That’s right. My father just turned ninety. We had a large birthday party for him about a week ago. Everybody was there, and we all talked about it. It’s one of those things, you want to live life with no regrets. There’s something that I didn’t do one time that I regretted that my brother went and did: a funeral that he went to, but I never went to, and it’s something I’ve regretted all my life. But, I always felt that, because he went, a little piece of me went with him. So, I feel like I was coming for my family and bringing a piece of them with me to see the painting. Everyone who was there at the party felt so emotional about missing out. No one has seen it since it left the house that day.

‘Living with this art was so special growing up’ recalls Patti Adler

Eric Merideth

Even before we bought it, Blue poles had its influential champions, America’s Frank O’Hara leading the charge. In 1951, he described it as ‘the drama of American conscience, lavish, bountiful and rigid’. He said it was ‘one of the great masterpieces of Western art’, and went on further to say it was America’s ‘Raft of the Medusa [1818–19, Théodore Géricault] and … Embarkation for Cythera [1717, Jean-Antoine Watteau] in one’. But what was it to you growing up? Did you have a sense of that when you were a child?

Patti Adler

Living with this art was so special growing up. My dad was also into classical music and used to have small orchestra ensembles come play in the living room. We had an amazing living room worth of art. Anyone who would come to my house would have their breath taken away because it was so stunning and so spectacular. There were so many people coming through the apartment because, in the early years particularly, the museums didn’t have American art collections. The dealers and the museum directors would bring people from other parts of the United States and from Europe, gallery owners and museum curators, to the apartment to see the finest works of Abstract Expressionism.

And, in addition to the paintings, he collected a lot of antiquities, sculptures of Indian, Cambodian, African, Egyptian works. These are all in together. It was a really amazing collection but living with these things is different from seeing them in a museum. Because, I think, when you’re grown up, you might say to yourself, ‘Nobody really owns art, art is for everybody’, but when you’re a child you don’t feel that way. When you’re a child, you feel like you own it. And to live with it made it a part of the fabric of our lives every day. We took our portraits every year in front of it, and we would sit and talk about it. It was really special. It was very intimate.

Eric Merideth

You mentioned the antiquities. I was reading something your father wrote for MoMA on his collection, about being a collector. He said there how they collected antiquities and then started collecting contemporary art, and they had a really troubled beginning with it. They bought a few pieces and then got rid of them. It took a little while for them to learn how to experience it. I was wondering whether you – also as an educator (albeit retired) – have any thoughts on that idea of educating people on how to experience art?

Peter Adler

I can speak as someone who walked in 1970 with eight of my friends, and we weren’t expecting to see this, and I knew right away that I was among masterpieces. I thought, becoming a member of the family, I better start reading really fast. Even though Patti says these were after the days that people said kids could have done it, people were still making fun of it and saying that it’s just work that wasn’t even thought out and things like that. I think, even to this day, we’re educating people that still say, ‘I don’t get it’.

The power, to be in that living room with four Rothkos and two Pollocks, it was just amazing. You can’t really describe that. That’s why Patti’s dad felt that it had to be in museums, where there were people who did know about it and who could describe it and explain to people how it was made. It was really important to him. He expressed that to us just last week. He really feels good about this. There were people who thought he was crazy to give it [One] to MoMA.

He has a few little pieces left from some of these artists but really not very much. He did sell some. He was basically a collector in the early days, and his dad was in the textile industry. He took over that company and then sold it and went into art dealing. But, from the forties to the seventies, he was an art collector, and he wasn’t really looking to make money. With Blue poles, he said to us, ‘I wasn’t Rockefeller. When they offered that kind of money, at some point, I had to say, “Yeah, I have a family”’. It was a business deal but, obviously, as you can tell from Patti’s voice, it was much more than a business deal. The emotion involved for him to make that decision was tremendous.

Patti Adler

Even just last week, we asked again, ‘Why did you sell it?’, and he said that he felt he wanted to grow as a collector and experience new works.

Peter Adler

In fact, he went to Alfonso Ossorio, another collector [and painter], to buy another Pollock – he thought he could buy it for some of the money he got for Blue poles – a piece called Lavender mist 1950, which he loved. But, eventually, Ossorio never sold it to him. He was able to buy other art, obviously, to keep his collection going, but that was the painting he had on his mind when he sold Blue poles. Ossorio lived in the same neighbourhood as he did, and he was friends with him. He thought he could talk him out of it but he wasn’t able to.

Patti Adler

It’s a passion, collecting. It really is.

Eric Merideth

He actually said once, about selling art, you sell works to bring in new experiences, and you can’t afford to have both.

Peter Adler

Exactly. Patti went to the Metropolitan Museum [of Art] with him last week and there was a [William] de Kooning there, and they passed it by, and he goes, ‘Oh yeah, I brought that home’, as if you bring home a piece of furniture. He said, ‘It just didn’t work for me’, and there it was in the Met.

Eric Merideth

Well, anything works in a gallery, doesn’t it, in a fashion? It’s much harder to curate the shows at home.

Peter Adler

I think you used it to refer to Patti, the phrase ‘having an eye’. I think, Ben Heller, he was the man who had the eye, along with Leo Castelli and a few other people. He was friends with these guys. He recognised them. He was a patron. They loved him because he loved what they did at a time nobody had that eye. In 1948 is when he bought his first work of art. He was twenty-two years old. He was born in 1925. And then that story Patti told you: his first Pollock at twenty-eight. If you look at it in history, it just seems improbable, this collection that a man amassed at such an early age. We all just toasted him at his ninetieth birthday, happy that he’s alive. Really, what he did for the art world, and for the world in general, it’s an amazing legacy.

We had this idea about a year ago to make this pilgrimage. We wrote a letter to Gerard [Vaughan, then Director of the National Gallery] back in March. He answered within twenty-four hours. Everybody’s been just so welcoming to us. We’re not Ben himself but we’re his emissaries. And we can’t be happier about how it’s turning out. We just thought we’d walk into the museum and look at it at first, without even telling anyone. But, that it’s coming at this time [so near to Ben’s ninetieth birthday], we’re just tickled and it’s really the highlight of our lives, this day.

First published in Artonview, no 84, Summer 2015

Historical photos published with permission of the Heller family

More